Para la versión en español, cliquea aquí

Synopsis

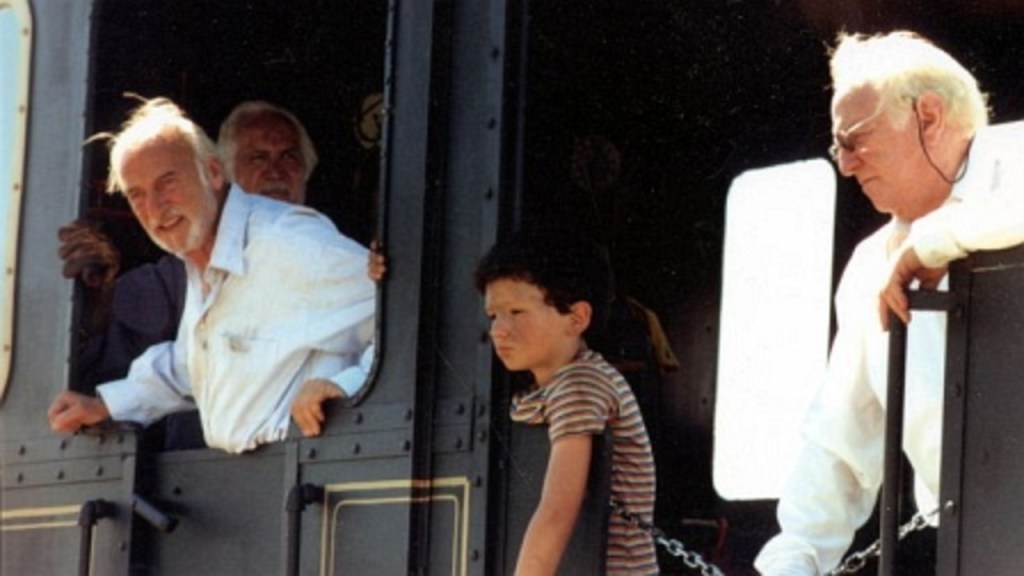

El Último Tren (2002) begins when three aging friends accompanied by a young boy decide to steal an old locomotive train that has recently been sold to Hollywood so that it can be used in a movie. On their voyage, they spread their message and explore the forgotten towns of the Uruguayan interior.

The mid-80s and 90s were particularly fallow periods for Uruguayan cinema. In fact, between 1983 and 1993, no Uruguayan films were even produced. This can be attributed to the embrace of free-market capitalism throughout the continent over the past decade. Following years of military rule, the 90s were marked by center-right policies that did little to change the economic woes of the previous decade and the already small movie business was in need of some serious revitalization. So, in 1994, decree 270/994 created the Instituto Nacional del Audiovisual (INA) and in 1995, the Fondo del Fomento y Desarrollo de la Produccion Nacional Audiovisual (FONA) was established in order to provide 10% of the budget for Uruguayan feature films.

However, the previous void in Uruguayan cinemas had to be filled by American productions rather than their own. As fewer films were being made in Argentina at this time, American stories dominated theaters and so American story archetypes were the ones that most filmmakers in Uruguay would be exposed to like the classic American road movie that director Diego Arsuaga makes his own with El Último Tren. The American road movie which is usually used to share stories of individuality and freedom, is given new life at a precarious time for Uruguayan cinema and culture. In 2002, the year of Arsuaga’s film’s release, Uruguay faced its worst economic crisis in years so the question remained: is it worth fighting against economic dependence in society and cinema or is progress a long way away? For the old men who make up the protagonists of El Último Tren, there is only one clear answer.

Every small act against outside influences looking to subjugate the country is worthy of celebration. Arsuaga aptly numbered the Locomotive with “33” an extremely patriotic number as it references the 33 revolutionaries who fought against the Brazilian invasion. Even choosing a train to steal rather than a car carries a lot of weight as it harkens back to a time of both economic prosperity and subordination. The railroads were a product of the British and represented Uruguay’s European nature. It is also a reminder of the industrialized export economy that grew in the early 20th century. Most of the old trains in Uruguay are not, in fact, passenger trains but freight trains, meant for products the British felt were more important. Over the years, they became obsolete symbols of a bygone era. This is why these members of the Amigos del Riel decide to designate the Locomotive #33 a national symbol that cannot be sold, even hanging a sign on it that reads, “El Patrimonio No Se Vende” or “Heritage Is Not For Sale”.

This fight for heritage is much more romantic than it is realistic. They often compare this mission to one from a Bradbury story where a brave knight bursts through a time portal and charges at a train thinking it’s a dragon. Of course, they are doomed but that does not diminish their courage. Both Pepe (Federico Luppi) and el Profesor (Hector Alterio) refer to themselves as knights and to Locomotive #33 as their black beauty as though this was a romantic adventure story and not real life. This is not a car chase and there are no backroads to escape through. All they can do is follow the track and hope that the businessmen will be forced to renege on the deal before the tracks run out.

As El Profesor would put it, their journey was “irresponsible but poetic”. What can you expect from a couple of men who spent their youth fighting in the Spanish Civil War, the ultimately doomed idealist struggle? Pepe even learned about how to conduct trains while fighting this war and so this locomotive is inextricably linked with the futile but vital fight for freedom against fascism. The romance of their journey is further highlighted by the vast open spaces they explore in the interior of their country. The hillsides and greenery that have long been abandoned with the end of railroad travel are testaments to the untouched beauty of their nation. One of the first people they come into contact with on their trip are gauchos, the ultimate symbol of the untamed and unmatched attractions of the River Plate.

This vibrant cinematography is starkly contrasted when the audience meets Jaime Ferreira, who is aptly given the anglicized nickname “Jimmy”. While the greens and blues of nature surround our protagonists, Jimmy lives in an affluent, all-white house that is opulent but extremely boring. This sets him up, not only as nothing but a businessman, but a traitor to the country. His only allegiance is to money. He does not even respect the police and sets himself up as the head of the investigation, interrogating suspects and chasing after the train, even though his only qualifications are his bank statement.

Jimmy is a lone figure fighting for money, but our train robbers express solidarity with each other no matter how much they disagree on petty things. They will not betray each other or their cause. Even when Jimmy offers to pay for El Profesor’s treatment for a heart condition at the Mayo Clinic, he flatly refuses, saying he needs to be seen by a doctor who speaks his language. While Pepe applauds this refusal, he also makes it clear that he has to get surgery immediately. He won’t let his friend or his ideas die. While they are unable to take their train across the border, they do manage to sway the hearts and minds of their country who show solidarity with the cause in their own ways, whether through taking in the third member of the group, Dante, whose dementia makes it impossible for him to continue on the journey, or forming a bucket chain to fuel the train with water.

These are the actions that make hope for the future possible. Pepe’s great-nephew, Guito is further proof that the future is bright no matter what. When questioned by news media if he was kidnapped and forced onto the train, he proudly defies them and says he chose to be there and do what any patriotic Uruguayan would have done. Many more Uruguayans heed his call and when Pepe and el Profesor are finally forced to cut their journey short, they are surrounded by a crowd of people ready to cheer them on and sit on the tracks, making it just that much harder for Jimmy to return it. In tough times, Diego Arsuaga reminds his audience that the battle may seem unwinnable, but there’s no harm in trying.

One response to “Fighting Globalization in El Último Tren”

[…] For the English version, click here […]

LikeLike