Para la versión en español, cliquea aquí

Synopsis

Midaq Alley (1995) looks at the intersecting lives of residents of a close-knit neighborhood in Mexico City. Based on the Egyptian novel by Naguib Mahfouz, this story follows a young woman confused about her first love, young men with dreams bigger than their hometown, and much more.

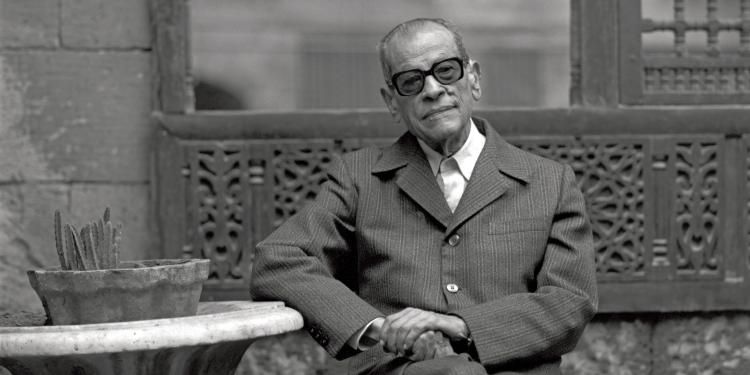

It’s hard to imagine how a book from 1947 that detailed the trials and tribulations of a historic neighborhood in Cairo could or should be adapted for contemporary Mexican audiences, but this decision turned out to be a stroke of genius. The author of the original novel, Naguib Mahfouz, was a forward thinker who used the backdrop of a chaotic neighborhood in the heart of Cairo to tell the story of a country and a people on the precipice of change. While in 1947, the rest of the world had just experienced an upheaval, Egypt was getting ready for one as the revolution of 1952 was on its way. The late 1940s were the last years of British occupation in the country and a new era of Pan-Arab nationalism would begin.

The Mexico of the mid-1990s knew exactly what that kind of overnight change was like. A year before Midaq Alley’s release, several major political changes occurred. In January of 1994, a military guerrilla group, the EZLN, began an insurrection movement in the Chiapas region, in the name of protecting indigenous people. This was in response to the recent implementation of the NAFTA trade agreements which some lauded as a policy that made trade easier and others criticized as a method for American companies to overwork Mexican laborers tax-free. That same year, the nation saw several political candidates assassinated, which would eventually culminate in the end of the ruling party, PRI’s, 71-year reign in 2000. The citizens of Mexico City were in the midst of a whirlwind of change.

In fact, even Mahfouz’s style translates easily into Mexican culture. For as long as cinema has been alive in the nation, melodrama has been a key part of storytelling. In the Golden Age of Mexican cinema between the 1930s and 1950s, most of the best films were melodramas so it is often hard to separate the genre from the Mexican national identity. However, this connection was not always praised by critics who viewed the genre as inferior and often complicit with suspect ideological structures in Mexico and abroad. By the 1990s, audiences and critics alike were beginning to see that the melodrama had much more to offer than just soap opera antics. The melodrama was a tool to exaggerate and critique the ills of society, especially toxic masculinity and the treatment and often disposal of women.

With two of its central characters, Don Rutilio and Alma, Midaq Alley examines the effects of these social injustices as well as their use throughout Mexican cinema. Don Rutilio or Don Ru, as he is more commonly known, owns the local cantina, a hyper-masculine space where men come to drink beer and play dominoes. Because of this, Don Ru spends most of his time desperately trying to perform his masculine duties in front of his male friends and customers. This involves anything from heavy drinking to referring to his son, Chava, as a “puto” because of his close friendship with Abel. All of this is, in fact, a way to distract from his own predilection for much younger men.

This mask only begets violence. Don Ru ignores his wife and projects all of his shortcomings onto his son who then beats Don Ru’s lover, Jimmy, upon finding them together. This all leads to Chava fleeing the country for the United States with Abel and Don Ru beating his wife simply for now knowing about his private life. Don Ru is not ready to confront who he really is and he will use any violence to prove it. This storyline is almost reminiscent of another Mexican film, Y Tu Mama Tambien, in which two young friends take a road trip with an older and sexier Spanish woman and end up sharing a homoerotic experience together. The morning after, however, they are clearly not ready to confront this fact about themselves and their friendship ends there. This story will not end with Don Ru living his life in the open or his family accepting him. All it leads to is escape and more violence and distance.

Whereas in the novel, many of the protagonists like Husain, Abbas, and Hamida, face the harsh reality of having to live under the thumb of British soldiers, our Mexican counterparts live under a form of US influence that separates families. Chava and Abel leave behind their family and girlfriend respectively in order to find wealth and opportunity across the border. This moment catalyzes a severe change for Salma Hayek’s virginal character, Alma, who now has to wait indefinitely for her love to come back. She is pushed in either direction between tradition and modernity. Will she wait for the penniless but hopeful Abel, become the wife of the unglamorous but stable Don Fidel, or drive off with the mysterious rich man, Jose Luis?

After a brief courtship to Don Fidel which ends suddenly when he dies of a heart attack, she chooses to go with Jose Luis and becomes what many women in Mexican melodramas become: a fallen woman. While Jose Luis seduces her with his extravagant lifestyle, it soon becomes clear he is not looking for a mistress, but an employee in his high-class brothel where he describes that women aren’t “putas” but “courtesans”. This trope is so common in Mexican cinema because it represents a straight line from the original violated maternal origins of the country to the present day. But beginnings don’t necessarily predict endings. When Abel returns from the US, he brings a mariachi band to greet his sweet and innocent love, only to find that she has gone missing.

Like any hero, he tries to find her and save her, but fails. On his second attempt to save her, he is stabbed by Jose Luis and subsequently taken away by Alma. She finds a way to save herself and him. Her ending with Abel is much more ambiguous than Don Ru’s. As the two lie on the street having narrowly escaped the brothel, he sits in her arms bleeding, and asks her to stay just a little while longer before she calls for help. While in Naguib Mahfouz’s novel, he dies in her arms, the movie leaves this ending wide open. Maybe Alma’s ending isn’t predetermined. Not every rule of melodrama needs to be followed and the new Mexico of the 1990s will challenge the status quo.

One response to “Midaq Alley: From Egypt to Mexico”

[…] For the English version, click here […]

LikeLike