Para la versión en español, cliquea aquí

Synopsis

La Bella del Alhambra (1989) takes place in Havana in the 1920s and 30s and follows the rise of a young theater star named Rachel. Though she has the talent to become the biggest star in her country, politics and personal turmoil threaten her place in the famous Alhambra Theater.

It’s hard to underestimate just how popular La Bella del Alhambra really was. Made as an homage to Cuban theater by Enrique Pineda Barnet who is most famous to international audiences for his work as a screenwriter on the Soviet-Cuban collaboration, I Am Cuba, this film practically caused a national delirium upon release. On an island of ten million, it sold three million tickets, became the first Cuban film to win the Goya Prize for Best Iberoamerican Film, and made its lead Beatriz Valdes, an instantly recognizable star. What was it about this particular movie that caught everyone’s attention? It must have caught its Cuban audiences’ attention from the first shot where we see a luxurious house filled with old furniture, antiques, lots of dust, and memories. We then hear Rachel tell her story about her glorious past goneby in the turbulent 20s and 30s. This time of excess that soon turns to destruction was familiar to Cubans who were gearing up to enter the Special Period when the Soviet Union collapsed and they were left in the economic wilderness. The story of the rise and fall of the Alhambra Theater where Cuba’s artistic identity was born could not have come at a better time.

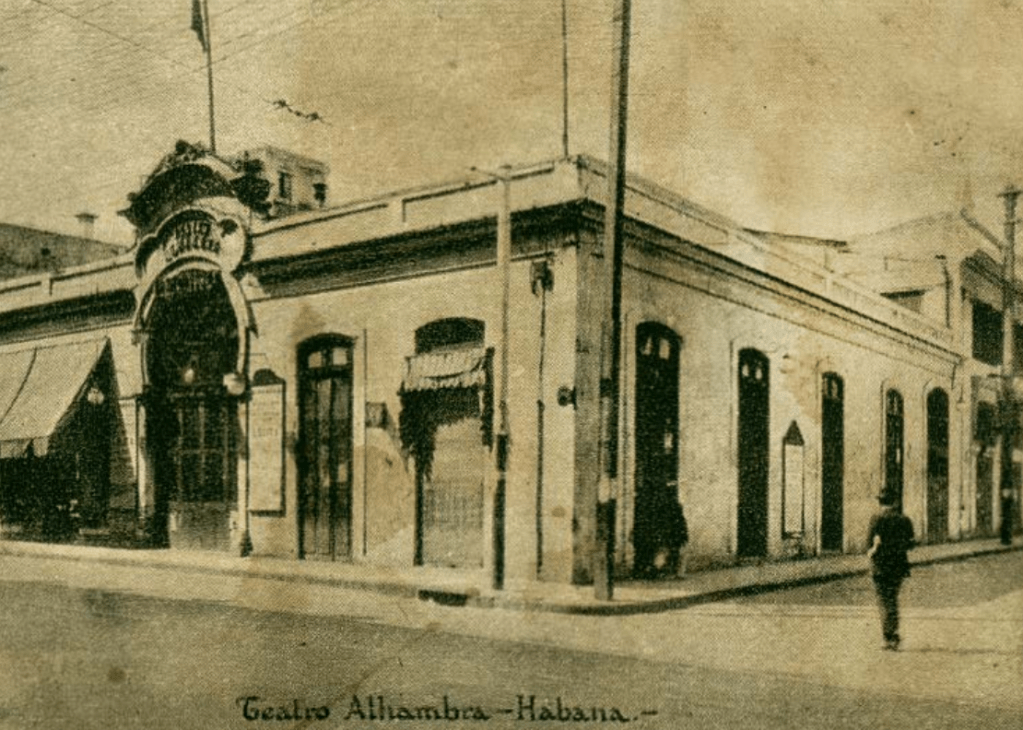

The Alhambra Theater was inaugurated in 1890, just before the Cuban War of Independence and lived its heydey in the 20s and 30s until it was demolished in 1935, only 2 years after Cuba’s infamous president Gerardo Machado was thrown out, and so the two are inextricably linked. Machado began his reign in 1925 and many were initially optimistic, especially US government officials who enjoyed a cozy relationship with the president. He created urban renewal programs and saw the economy grow, but with the Crash of 1929 came economic depression as well as vastly falling sugar cane prices. Intense political repression followed and heinous murders were carried out by police leading to mass protest until even the US could not back Machado anymore and he resigned. The Alhambra drank in all the excess and delight of the decade that just couldn’t go on.

Even its star Amelia Sorg who became the basis for this film as well as the novel Cancion de Rachel, quickly faded into obscurity. Though she was born in New York City, she came to Cuba in 1898 just as they had earned their independence from Spain and went from choir girl at the Albisu Theater to a star at the Alhambra. Though only loosely based on Sorg, the film’s protagonist, Rachel, faces a similar trajectory, but hers is even more intertwined with the idea of what it means to be Cuban. Initially a poor choir girl in Havana, Rachel lives and dies by the diverse Cuban theater traditions and like any resourceful and ambitious islander, breaks the rules along the way.

Rachel gets in everywhere through the backdoor. When she first hears that her inspiration and later rival, “La Mexicana” is performing a risque, men only show the Alhambra Theater, she does the only thing she can: she crossdresses. Then, when she tries to replace “La Mexicana” as the biggest star in Cuba, she learns how to perform from Afrocuban dancers who show off their moves on the street, not in the theater. She then neatly repackages that dance style in a surprise performance she gives after sneaking into a ball filled with high society folk. Though she earns the adulation and patronage of rich men, she never plays it safe. When she finally gets to perform as a star, she crossdresses again as a Zorro figure, kisses a man, then strips off her top.

It’s an incredibly scrappy but audacious rise to fame, and one that hinges on Cuba’s complex racial identity. She brings the Afrocuban dances and style off the streets and into the theater but she also tells their story without their involvement. In order to gain her own fame she has to bargain with other people’s recognition. Rachel not only tries to be adjacent to Black Cuban communities but appear more American with flapper routines as well as more Operatic European ones. Like Cuba, her art is due to a mix of colonization and appropriation.

But while Rachel begins this story with a lot of hope, rising up thanks to the abundance of artistic support around her, her story will end tragically. As Pineda Barnet put it, she, like her country, is someone wh otries and fails to not be prostituted by more powerful forces. On her rise, she is buoyed by a loving stagehand, Adolfito, who literally shows her what a star she can be by practicing moves with her in the mirror. His adoration can only get her so far, and soon she has to drop him for richer men who don’t try to preserve her talent. The next time, she dances with a man in the mirror, he ends up fighting with her and shattering it along with her self worth.

Her love life is littered with tragedy. As Cuba begins to rack up political prisoners and dead, so does she. Her first great love, Eusebio, kills himself after succumbing to the impossibility of their love and Adolfito, once dropped by Rachel, becomes homeless and tragically dies in a haze of bullets while being used as a shield for one of the rich men who propped her up. Though she tries to find love in the arms of men, the only love she stays loyal to is that of the theater. Even as her world falls apart, even when her theatrical passion stands in direct opposition to her romances, she still chooses it.

Almost as soon as Machado resigns, the theater closes as a new political era begins as well as a new era in entertainment. The Cuban cinema takes over and Rachel’s career is obsolete. But the Alhambra Theater is not the Copacabana and this is not the story of a woman driven crazy by heartbreak and frozen in the past as it might have appeared in our opening shot. The same shot of her untouched apartment appears at the end as Rachel tells us that though she has never understood politics, she does understand the Cuban people. Through good times and bad, they have survived with drums and beer. Looking down the barrel of one of the worst economic times since the revolution, Pineda Barnet asks us to look back. Yes the Alhambra became a relic of the Machado era that was destroyed by cinema, but it was also revived by it. Whatever happens, the Cuban people will always have their drums and beer.

One response to “Cuban Identity in La Bella del Alhambra”

[…] For the English version, click here […]

LikeLike