Para la versión en español, cliquea aquí

Synopsis

Actas de Marusia (1976) tells the real-life story of the Marusia Massacre in which several hundred miners were killed as part of a state retaliation for their strike. The movie follows union leaders, Gregorio and Soto as they round up workers and face unthinkable repression.

On August 16, 1977, a group of Chilean filmmakers wrote an open letter to the military government’s Secretary for Cultural Relations asking for state aid to be given to cinema. They expressed the dire nature of this request by stating “Cinema is doomed to die here very soon.” Ten years earlier, that statement would have been preposterous but after only a few years under Pinochet’s ruthless government, it was an understatement. Before the 1973 Coup, cinema in Chile had not yet found a voice in the same way that Cuba or Brazil had in the 1960s but they were on their way. With new faces in politics, music, film, and literature, Chile’s future looked bright. Speaking at a conference in Venezuela in 1974, director Miguel Littin declared, “More novels and essays were published and read, more music recorded, more murals painted, more exhibitions minted, and more theatre and dance companies founded than at any other time in the country’s history.”

President Salvador Allende’s ousting stopped everything in its tracks. Every film school, studio, or distributor became occupied by the military, and censorship laws made it nearly impossible to make a film that adhered to Pinochet’s guidelines. Even if the rules had not been so stringent, there were barely any accomplished artists available to create films. Many filmmakers had been killed in the coup’s resulting violence and most others fled. Famously, Argentine cameraman Leonardo Hendrickson filmed the shots which killed him during the attempted ‘Tancazo’ coup on June 29, 1973. Those exiled may not have faced the imminent danger of their compatriots but they faced an aimlessness that threatened the lives of many. As Littin later wrote, “Exile is one of the worst things that exists because it dries you up inside and makes you lose the desire to live.”

Still, the artists that were able to turn their sadness into a wave of determined anger created some of the best works of Chilean art outside of the country’s borders. The coup took livelihoods and lives away from many, but created a sense of urgency and identity to a film movement that had been in its nascent stages at home. The Chilean film industry lived on in exile. While Chileans in Chile were bemoaning the state of their art, exiled filmmakers like Pedro Chaskel, the editor of La Batalla de Chile, wrote “Chilean cinema is alive.” One of the shining stars of this exile community was Miguel Littin. Littin made a name for himself in Chile for his controversial true crime film, El Chacal de Nahueltoro, but while in exile he created some of the best work of his career including two Oscar-nominated films: Alsino y el Condor and Actas de Marusia.

His first film made entirely outside of Chile, Actas is a pan-Latin American effort that works so well because it is the sum of very diverse parts. By connecting countries, time periods, and even gender, Littin creates a powerfully relevant epic. Though Marusia, a now barren mining town may seem devoid of meaning outside of Chile, its story transcends history and space. This is literally the place where most early cinematic stories were born. Without the nitrate it provided, early directors would have nothing to film on. After years of sourcing stories for others, it was time for Marusia to tell its story. In 1925, the workers of the Marusia nitrate mine decided to strike, during which a brutal British engineer was killed. A Bolivian worker was subsequently accused of murder and executed without due process. The union leader Soto, afraid of reprisals, decided to contact other mines to blow up the railroad tracks and arm the whole town. The action, unfortunately, ended in the death of at least 500 miners (though the exact number is not known) and led to the La Coruña Massacre two months later.

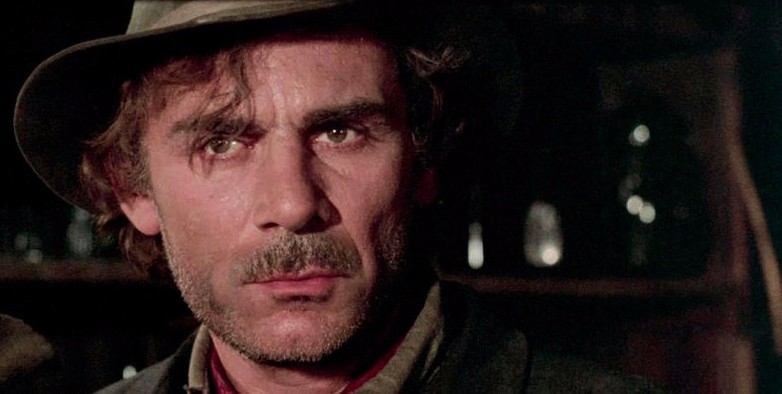

Based on the story of a band of miners from all over Latin America, Littin’s exile, serendipitously, made the movie as authentic as possible. With a cast of Mexican actors, a Chilean crew, and an Italian lead, everyone was able to bring their own unique experiences to the movie and made it their own. The lead, Gian-Maria Volonte was a famous political activist as well as an actor who was known for his communist leanings. Later, it was even revealed that he aided in the escape of famed Marxist intellectual, Oreste Scalzone, to Denmark. Many of the Mexican actors had come from mining towns as well and according to Littin, “In one way or another, they had similar experiences to the ones I intended to portray in the film. I can’t conceive of any other way to make cinema for the people, if not by taking into account the opinion of those people.”

It had to connect across Latin America because the nature of this strike was not insular. Marusia’s union leaders wanted to spread the word across Chile and the film takes the time to explore the diverse groups of miners in the country. In one of the most harrowing scenes, a train full of soldiers passes by a crazed group of beggars. They are simply called “sulfates”. After two or three years in the sulfate mines, the fumes drive them insane and they are doomed to a life of madness. Though they never meet Gregorio and Soto, it’s important their story is told. The same goes for the story of the Iquique Massacre which is told by Marusia’s schoolteacher who had witnessed the event. For Littin, connecting struggles through time and space was the most important job.

It’s the reason he did not simply tell a story about Pinochet’s violent coup. Littin believed, “it is impossible to make a movie about the defeat of the Unidad Popular because it is impossible to make a movie about any fact that is too close to home.” Taking the story to another time allows for a deeply frightening foreshadowing. When Chilean army captains describe how many American instructors they have and comment on the slow invasion, it’s eerie. And when we see bombs exploding the houses and buildings of Marusia, it’s impossible not to think about the bombing of La Moneda. We know the destruction that is coming before they do so Littin is able to create the most tragic irony. When the workers say they can still negotiate because there is no way the bosses would bomb Marusia, we know even before it is declared that that can’t possibly be true. It’s the natural progression. Just as the cavalry of local soldiers soon turns into a train full of military squadrons, the modern world brings more tools for destruction.

That being said, Littin doesn’t paint an entirely dreary picture. He also shows how inclusive organized struggle can be. It’s not only important to connect your personal struggle to other nations and time periods but across gendered lines. The women of Marusia are just as involved as the men. They create a whisper system to inform the town of new developments and are present at every execution to intimate the soldiers. They even use their presumed victimhood to their advantage. In order to stop a train full of soldiers from entering, they are willing to lay their bodies down on the train tracks. The image of the damsel in distress tied up on train tracks is as old as film itself. But in Littin’s version, these women don’t need saving and it is their body that is the dangerous weapon.

Like its predecessors, The Organizer and The Battle of Algiers, Actas de Marusia is an optimistic film that still understands the limitations of armed struggle. Gregorio declares that for every strike won, ten are lost. This attitude keeps the film grounded but still allows audiences to leave the film feeling inspired. Though by the end, Marusia has been bombed out and Gregorio has been captured and tortured, the hope is not lost. Soto and his friends have escaped with Gregorio’s written account of what happened in Marusia. Marusia may be dead but its story remains alive.

One response to “Exiled & Exalted: Miguel Littin’s Actas de Marusia”

[…] For the English version, click here […]

LikeLike