Para la versión en español, cliquea aquí

This week we’re focusing on Mexico and machismo… my favorite subject. To anybody reading this, please be kind to me if my Mexican Revolution summary is off. This shit is very complicated.

Synopsis

Vamonos Con Pancho Villa (1936) follows six friends who decide to join the fight with Pancho Villa. At first, they are proud to be a part of the struggle, but one by one they fall showing the futility of war.

The Mexican Revolution

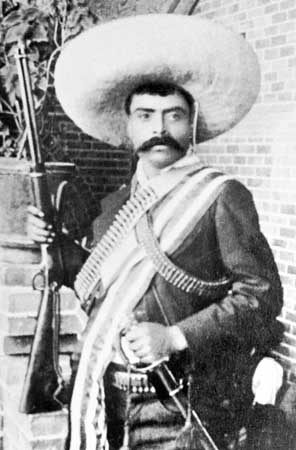

Porfirio Diaz ruled Mexico for 27 years as their dictator, but the economic progress of Porfirian Mexico excluded most citizens. Foreigners benefited most from Diaz’s reign with foreign capital controlling an estimated 67 to 73 percent of all capital invested in Mexico. By the beginning of the 20th century, dissatisfaction grew and unpopular local leaders fostered unrest and resentment toward the government. Then in February 1908, Diaz held an interview with an American journalist and told of his plans to retire in 1910. He explained that Mexico was capable of democratic action and opposition would be welcomed. Most politicians chose to stay out of the race because a direct challenge to Diaz was too much of a risk. Almost immediately, Francisco Madero was a prime candidate. He sought political reform but before the elections could take place, Madero was jailed and fled to the US where he presented the Plan de San Luis Potosí, declaring that the election had been fraudulent and that he was assuming the presidency. By May 1911, rebel forces surrounded the federal army at Ciudad Juarez resulting in their surrender. Diaz resigned to exile in France and Leon de la Barra was appointed provisional president until the October 1911 elections, but now Madero was not the only opposition leader. Emiliano Zapata had become a major figure. He was from Morelos and unlike many rural Campesinos he owned a small piece of land. When he took a job as a horse trainer in Mexico City he found that many horses lived better than his own neighbors.

Zapata split with Madero because he called for the complete surrender of rebel forces in Morelos. Still, Madero received the US ambassador’s support and won with 98% of the vote. He initiated policies to address the divisive issues between owners and laborers but at the end of the day Madero favored stability and did not carry out a lot of his liberal goals. Revolutionary factions began fighting against him, most notably when Zapata spoke against Madero with his Plan de Ayala in November 1911. Zapata’s actions opened a floodgate and many more spoke out. Madero turned to Victoriano Huerta to suppress the rebellion but he joined the rebels, arrested Madero, and forced him to resign. Huerta assumed office and on February 21, 1913, Madero was dead, though the circumstances remain unclear. Initially, Huerta appeared to be in control. Zapata’s forces seemed small and isolated but soon things changed.

On March 26, 1913, Venustiano Carranza announced the Plan de Guadalupe, refusing to recognize Huerta. Carranza and his supporters became known as the Constitutionalists. Mexico was split between three military factions: Huerta, Zapata, and Carranza and the US declined to grant diplomatic recognition to Huerta’s government as President Wilson favored Carranza. The US ended its arms embargo and allowed the Constitutionalists to obtain weaponry. Huerta stepped down as president and went into exile in July 1914 and Carranza claimed control. He called all the revolutionary delegates to a meeting in October 1914 and negotiated between Carranza’s own desires, the land reform issues of Emiliano Zapata, and the conservative goals of Pancho Villa.

By the end of the convention, the delegates dismissed Carranza as head of the revolutionary movement and named Fulalio Gutierrez as interim president on October 30, 1914. The Constitutionalists fled Mexico City and both Villa and Zapata claimed the capital. The split between the two was too big and Carranza’s Constitutionalists took advantage of this and targeted Villa who fell in April 1915 at the Battle of Celaya against Constitutionalist general Alvaro Obregon. Carranza continued absorbing political rivals and sought support from the leading labor institution established under Madero, Casa del Obrero Mundial. With their support, he defeated Villa and Zapata and in March 1917 Carranza won the presidential election and assumed office in May with his major accomplishment being creating a national labor union, CROM, though many divisions within this union remained. Strikes continued to break out across the country because of unenforced labor laws and Emiliano Zapata issued an open letter to Carranza in March 1919 charging that the goal of the revolution–to benefit the masses– had been violated by Carranza. Zapata was later killed. Led by Alvaro Obregon, the Plan de Agua Prieta was presented to the nation in April 1920, denouncing Carranza’s intentions and demanding his immediate resignation. CROM leadership sided with Obregon. Carranza seized as much gold as he could and fled to Veracruz by train in an attempt to exile. He was caught and executed by a member of his entourage whose loyalty was actually with Obregon. The revolution was finally over.

Pancho Villa

Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa was born Doroteo Arango on June 5, 1878, in San Juan del Rio, Durango. When Villa’s father died, he assumed the role as head of household. He shot a man who was harassing one of his sisters in 1894. He fled, spending six years on the run in the mountains. In the late 1890s, he worked as a miner in Chihuahua and started robbing banks. In 1910, Pancho Villa joined Francisco’s Madero successful uprising against Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz and his company won the first Battle of Ciudad Juárez in 1911. Madero took the presidency and Villa was named colonel. His relationship with Victoriano Huerta soon soured though and after Huerta accused Villa of stealing his horse, Villa’s execution was ordered. As Huerta rose to power, Villa teamed up with a former ally, Emiliano Zapata, and Venustiano Carranza to overthrow the new president.

Villa controlled much of northern Mexico’s military forces during the revolt. This gave him more of a spotlight from the US media and he even signed a contract with Hollywood’s Mutual Film Company in 1913 to have several of his battles filmed. He stood in stark contrast to Zapata. While Zapata represented the Campesinos, Villa dressed in outfits worn by Americans and Europeans. He felt more comfortable in the capital. Carranza rose to power in 1914 and Woodrow Wilson withdrew his support of Villa the following year, leading to Villa kidnapping and killing 18 Americans in January 1916. Only months later, on March 9, 1916, Villa led several rebels in a raid of Columbus, New Mexico, where they ravaged the small town and killed 19 additional people. Wilson retaliated by sending General John Pershing to Mexico in order to capture Villa. De la Huerta negotiated with Villa for his withdrawal from the battlefield. Villa agreed and retired as a revolutionary in 1920. He was killed three years later on July 20, 1923, in Parral, Mexico.

Men and Death

When the men of this film join the fight, they almost immediately start talking about death. One night they discuss their plans for their body and how they should be remembered. They are certain that in this war their death will not be a tragic event, it will be a heroic act but these ideas are based on an outdated machismo and a blind nationalism that unfortunately cannot come to fruition. I believe two particular deaths illustrate the tragedy of their unrealistic dreams. One of the first deaths occurs when Martin Espinosa dies in the midst of a battle. His actions before his death lead to victory in battle so the sadness his friends feel to see him go is overshadowed by Pancho Villa’s own victorious cheer and the bugle horns playing as the closing shot zooms in on Martin’s lifeless eyes. But the image of his dead body is even eerier since he is lying atop a maguey, an agave plant that is a symbol of Mexico. Though Pancho and his men are celebrating, the audience knows that his death is synonymous with the death of the celebrated culture and image of Mexico.

This downfall is finalized by the death of Meliton Botello. His death comes in a bar when the 13 men sitting at the table realize that one man needs to go to avoid an unlucky number. The men rationalize that in order to undo the bad luck they will sit in a circle and drop a loaded pistol. Whoever is killed is a coward and deserves it. Meliton is shot in the stomach and in order to avoid dying a slow unheroic death, he yells “Now you will see how a lion from San Pablo dies” and kills himself. Out of a need to put meaning into a meaningless existence, the men use this game to create a heroic scenario but are instead left with a tragic accident. Feeding their machismo, they can’t deny a chance to prove how good they are in this dangerous game. These deaths just serve as further reminders of the dangerousness of overblown pride and the tragedies it brings.

The Ending & Mexico’s Future

The film ends in an unceremonious and tragic death. When Becerillo falls ill with smallpox, Tiburcio is forced to burn his friend alive because Villa believes that the illness could infect the rest of his troop. Tiburcio wants to continue fighting but Villa callously tells him his services are no longer needed and he limps home without his youthful dreams of honor in warfare. The ending cements the director’s idea that war turns men into animals. In a death that followed four others, it has lost any glimmer of the ceremony. Tiburcio does not even try anymore to find meaning in his friend’s death. There is nothing good about this war. But I believe there is more meaning in the alternate ending. Adding onto this sequence, the original ending features a time jump of a couple of years. Villa goes to Tiburcio’s home and asks him to return to battle. Tiburcio refuses and Villa kills him, his wife, and his daughter, but takes his son with him. It is unclear why this ending did not make the final cut but many point to censorship. With this ending, the director Fernando de Fuentes suggests that Mexico’s future is also in peril. The violent and unstable world of the revolution has not been left behind and the children of these men are being corrupted with the same illness. To the new leaders of Mexico, will children continue to be sacrificed like animals or can you find a new way to unite the people? De Fuentes suggests that will be impossible and more will have to die in unnecessary wars and revolutions.

2 responses to “Mexico’s Revolutionary Epic: Vamonos Con Pancho Villa”

[…] For the English version, click here […]

LikeLike

[…] in my blog series on Mexico, I analyzed the Fernando de Fuentes classic, Vamonos con Pancho Villa. This classic film captures the disappointments of the revolution and the pitfalls of toxic […]

LikeLike