Para la versión en español, cliquea aquí

Synopsis

Tango (1998) follows Mario, a middle-aged theater director who throws himself into his new project, a musical about tango, after his girlfriend leaves him. When he finally puts on the production, he falls for a young dancer and the girlfriend of one of the show’s investors, Elena. As their love grows deeper, so do the dangers leading to the blurred boundaries between life and art.

When Spain fell under the control of the ruthless fascist dictator, Francisco Franco, many of their greatest artists fled. Spain would unwillingly give away one of their greatest filmmakers, Luis Buñuel, to France and Mexico where he made most of his films from the 1950s until his death. Many exiled Spanish artists continued to make art criticizing the government but Carlos Saura stands out as one of the few directors who stayed and fought, creating subversive art that may have made its way past censors but was just as crucial. Films like Cria Cuervos or Peppermint Frappe deftly condemned Franco, but after the regime ended, Saura had to change course. The dictatorship which had been the subject of much of his previous work was gone so he turned to dance. Making a Flamenco trilogy allowed him to explore a new genre and his own artistic identity in this transitional period. Though continents apart, Tango is a continuation of this conversation.

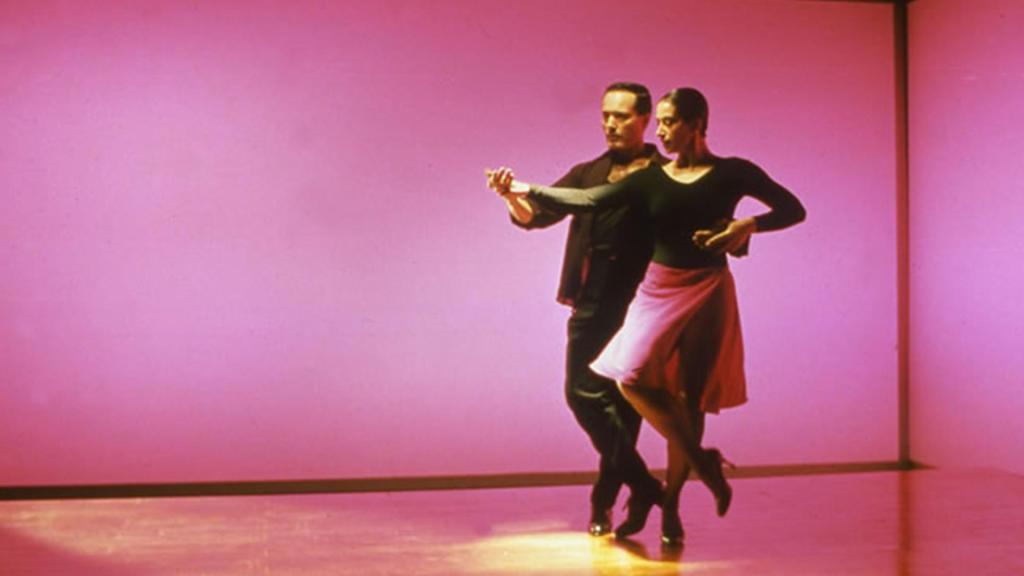

In Tango, the artistic process of theater director Mario is used as a mirror for Saura’s own work and as a form of therapy in the face of tragedy. This plays out almost instantly. Mario has just written his life story which will serve as the backdrop for the movie. He recounts his sadness that he and his girlfriend, Laura, are no longer together. His imagination takes over and we see a tango dance beautifully lit with a colorful background and silhouetted dancers. He watches over the two dancers, one of whom is his girlfriend, and before it comes to a close, he takes over and stabs her. The illusion is quickly broken when we cut back to reality. His girlfriend has returned home to pick up her things and tell him that she is with someone else. He can’t get the beautifully tragic and fiery climax that comes in the tango sequence. Instead, he begs her to come back and then pathetically attempts to force himself on her. Art gives him a space to act out his violent and unhealthy desires without causing any real damage. His real-life attempts to do so only embarrass him.

Because he cannot act on all of his true emotions and anxieties, his art becomes more real than his life. The constant use of mirrors throughout the dance numbers and in Mario’s own life are not there by accident. Saura is able to insert himself into Mario’s own story. Anytime the audience seems to be absorbed in the action, Saura brings out a mirror or even more obviously, a camera, to show his presence in the scene. This Brechtian technique is not used to jolt the audience out of the scene but to show just how real art can feel. Even when we see Saura’s own watchful eye, we still choose to focus on the dancers and the stories they weave. It also emphasizes the unattainable nature of resonant art. Mario has a leg injury that forces him to be a mere spectator rather than a participant in this show. As a director, Saura can never live in the worlds he creates, only watch. As Mario says, inspiration is really just work and the joys that it brings others are often built on the dissatisfaction and longing of someone else.

The artistic process is not stripped of all its beauty and flare but it is shown to be something built on unglamorous pain. The post-Franco era allowed Saura to meditate on his own identity as the previous era’s political urgency had not allowed for it and it also gave him the chance to focus on his own nation’s identity through odd channels. His Flamenco trilogy but particularly, Carmen tried to contend with what it meant to be Spanish now that Franco was not there to define it. Based on a French opera, Carmen had nevertheless become a symbol of Spanish identity. This French invention was interwoven with one of its most celebrated arts, Flamenco, in order to question this identity. Seen as a lower art that had been bastardized as a shallow symbol of patriotism by Franco, Carmen helped to elevate Flamenco as national art akin to ballet and used it to detail the country’s deep-rooted history of violence and subjugation.

Tango is another dance form that deserved that exact same treatment. After hoards of Argentinian exiles flooded European cities, the dance became seen as simply yet another seductive and exotic Latin dance. Its history and artistry had become completely separated from its international image. But the 1990s in Argentina not only saw the return of many exiles but the rejuvenation of the tango. It’s this fact that makes Carmen and Tango intimately connected. According to Saura, “There are affinities between Spain and Argentina. We share many things. I feel as much at ease in Argentina as in Madrid or Barcelona. We speak the same language and our traditions are similar. As a very young child, I used to listen to the music of Tango and Argentine songs: Carlos Gardel, Imperio Argentina… One can say that my contemporaries grew up listening to this music.” With a soundtrack from Lalo Schifrin, a composer who worked with tango greats like Astor Piazzolla and then moved on to Hollywood, writing the scores for films like Cool Hand Luke and Voyage of the Damned, the film infuses the old traditions with the new skills of its exiles. Saura even includes scenes of young tango singers redubbing famous tango singers as part of Mario’s show.

Saura shows the world at large that tango is not an ancient Latin mating dance but an ever-evolving art form and one that is not divorced from the country’s history or politics. Just as Franco used Flamenco to create a unified Spanish identity devoid of Romani, Catalan, or Basque influence, the tango was used to drown out the screaming of tortured dissidents. This street art had been corrupted. It’s this fact that leads Mario to choreograph a tango in which Elena flees from the police and hoards of executioners as well as another number that is entirely silent. When these numbers are met with confusion and distaste from a backer who believes that the show should only consist of beautiful women and dances, Mario quotes the poet Borges and says, “The past is indestructible; sooner or later everything comes back around, and one of the things that comes back around is the project to abolish the past.” If audiences thought they were going to see a story of passion devoid of any context, they are sorely mistaken.

Though Tango is eerily similar to Carmen, Saura subverts expectations where necessary. Carmen follows a visionary Flamenco choreographer and dancer who falls in love with his female lead, becomes increasingly jealous, and stabs her in a scene where it’s impossible to tell if the violence is real or staged. In Tango, Mario starts off as an aggressive and jealous ex who slowly becomes more calm and seems to trust Elena implicitly. It is the level-headed backer and Elena’s ex-boyfriend who becomes dangerous and leads her to believe he is following her. Apart from that, Elena is not a Carmen-type. She is sweet but not naive and her passion seems consistent and not flighty.

This mix of jealousy, passion, and desire culminates in a final tango number set on the Buenos Aires docks at the turn of the century as the immigrants arrive and dance the tango. At the outskirts of the scene, we see a man in costume watching Elena intently. He soon takes Elena away, dances with her, and stabs her. Mario limps toward her and holds her in his arms until she finally opens her eyes and asks if that was good. Saura does not leave us in limbo as he did with Carmen. Whereas that film’s ending connoted that while Franco was gone, the machismo and violence lived on, Tango’s ending says something different. By 1998, Argentina was 15 years away from its dictatorship era. Maybe they have gotten rid of the ills that plagued them. While the ending seems less ambiguous than Carmen, Saura chooses to conclude the story as the actors leave the stage and a lone camera appears. The story isn’t over quite yet. Though Elena and the nation are OK at the moment, it doesn’t mean that this ending will stay.

One response to “Tango: A National & Artistic Mythology”

[…] For the English version, click here […]

LikeLike